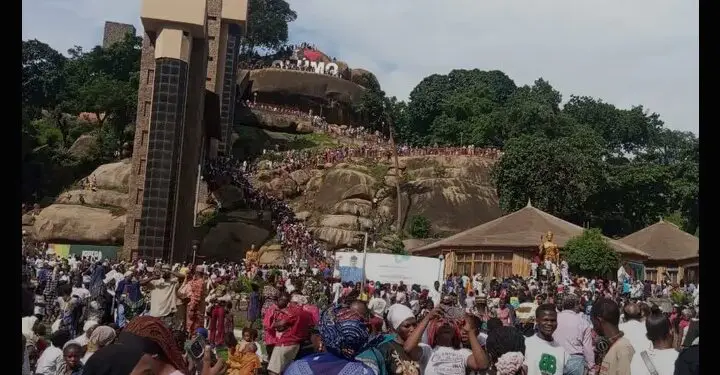

The foot of Olumo Rock was a hive of activity recently in Abeokuta, the kind of energy typically found at football championships or music festivals. Families holding water bottles prepared for the ascent, groups of teens waiting to take photographs against the mural-lined entrance, and children running between food booths. Visitors were crammed into the little stairways set into the old stone, and their voices reverberated off the walls. After the Ogun State Government decided to open its gates for free, this has been the situation at one of Nigeria’s most famous locations for weeks.

But beneath the joyous ambiance lies a more sombre reality: the monument’s 137-metre height has been strained by the overwhelming number of visitors. There have been times when rushing crowds have threatened to overrun the site’s fragile walkways, forcing security personnel to intervene. “The crowd was so crowded at one point that it might have become dangerous,” said an on-duty tourist official. “A stampede was our concern.” What was intended to be a kind gesture—free admission to Olumo Rock following renovations—has instead brought to light the delicate balance between maintaining public safety and granting access to historic monuments.

Olumo Rock, which translates to “under the rock” in Yoruba, is more than just a striking cliff face that overlooks Abeokuta. With its caverns and overhangs providing cover and strategic defence, it was used for generations by the Egba people as a fortification during intertribal conflicts. It is now a representation of tenacity and spiritual continuity. It is “a place of culture, a place where prayers are offered to God and are always answered,” according to Oba Adedotun Gbadebo, the Alake of Egbaland.

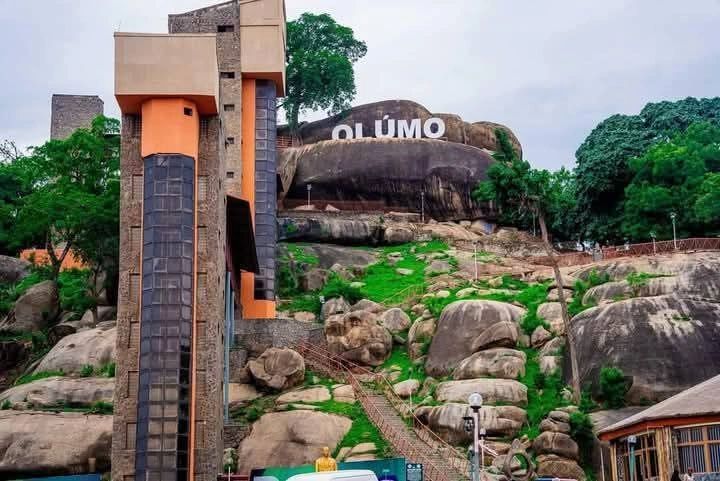

The facility was closed for refurbishment in April 2025. By July, it had returned with a revamped tourist complex that included a galleria with portraits of notable Nigerians, a new restaurant offering both continental and local cuisine, shops selling Adire fabric and—perhaps most remarkably—elevators to make the ascent easier for people who are less able to climb the rough stairs of the rock.

In order to revitalise tourism, empower young people through creative industries, and restore Ogun State’s place on Nigeria’s cultural map, Governor Dapo Abiodun presented the project as a component of a larger cultural and economic agenda. He declared that admission to the complex will be free through August in order to begin this project. Unrestrained enthusiasm greeted the move. Olumo Rock became well-known on Instagram and TikTok in a matter of days. In order to make the rock one of Nigeria’s most popular summertime locations, families from Lagos, students from surrounding colleges, and even foreigners posted their ascents.

With the goal of democratising culture, the free-entry programme gave all locals and tourists an opportunity to rediscover Olumo Rock’s roots. However, as the crowds increased, the site’s limitations became apparent. There was no way the tiny underground chambers, steep ledges, and winding staircases could hold thousands of people in a single weekend. Visitors were caught in traffic jams between climbing groups, according to tourism officials, and security forces had to erect temporary barricades to control the flow of people.

Eventually, the government stepped in. Governor Abiodun declared that free access would expire on Saturday, August 23rd, ahead of the originally scheduled September cut-off date, citing public safety. After that, regular ticketing will restart, and on September 4th, it will formally reopen as a tourist destination that generates income.

A bigger issue facing tourism is how to strike a balance between safe, sustainable heritage management and public excitement, which is reflected in the Olumo Rock episode. This problem is not unique. From Angkor Wat to Machu Picchu, locations all around the world have had to deal with the effects of excessive tourism. Cultural monuments are at risk of deterioration when yearly visitor numbers surpass their carrying capacity by more than 30 per cent, according to the United Nations World Tourism Organisation.

In Nigeria, the issue could be made worse by inadequate emergency preparation and infrastructure. Timed entrance procedures, visitor caps, and proper staff training for crowd control are absent from many heritage sites. For example, the new lifts at Olumo Rock might make physical access easier, but they might easily push more people onto the summit at once if there are no numerical limits. The pandemonium surrounding free entrance, according to tourism experts, highlights the need for a more calculated approach. From the lens of cultural economy, “It’s not enough to just open the gates.” There is a need to consider ways to control flows, safeguard the monument, and ensure the security of visitors. Otherwise, years of trust and investment could be lost in a single accident.

Moreover, the transfiguration of Olumo rock transports a pleasant aroma of prosperity for Ogun state. It is anticipated that local companies will prosper; weekends will be busier than ever; food vendors and Adire cloth vendors will dance to the bank. The large numbers show that heritage tourism may actually boost local economies, which is encouraging for a place that is frequently eclipsed by Lagos. But the dangers are still present. The reputation of the location and public trust in Nigeria’s capacity to oversee top-notch attractions might be severely damaged by a stampede or accident on the ledges of the rock. Heritage is fragile and we run the risk of losing what makes it unique if we don’t treat it carefully.

The litmus test will be the official reopening on September 4th. Access will be paid for this time, and a new online and in-person ticketing system will be used to control the number of attendees. Enforcing it will be difficult. Will Ogun State be able to strike a balance between the discipline needed to maintain Olumo Rock and the enthusiasm it has generated? If properly managed, the location might serve as a model for Nigerian heritage tourism, a place where visitors can safely blend spirituality, history, and contemporary experiences. But if poorly maintained, it could end up on the list of overworked monuments whose splendour is diminished by carelessness and shoddy design. For generations, Olumo Rock has served as a stronghold, a haven, and a historical site. Its granite walls narrate tales of community, faith, and survival. The influx of tourists this summer demonstrates that Nigerians still yearn to connect with their history and that, when shared, heritage can bring people together. The current challenge is to make sure that the need for access does not compromise security and that Olumo Rock’s legacy lives on as an enduring cultural and tourism icon rather than merely a viral moment. “Olumo has always protected us,” said an elderly pilgrim, leaning on his walking stick as he descended the cliff. It is now our responsibility to keep Olumo safe.